Golem

by Victoria Mack

The monster first appears in the shape of a small child, on an unseasonably warm winter day in New York City. It is late morning, and the windowpanes in Becca’s Washington Heights Elementary School classroom, already spotted with greasy fingerprints, are now clouded over with humidity. Becca hates feeling wet. She kneels on the rug, a brightly-colored illustration of the alphabet, in a circle of five-year olds. The children grip crayons in their clumsy hands like knives, stabbing at their drawing paper with feverish intensity.

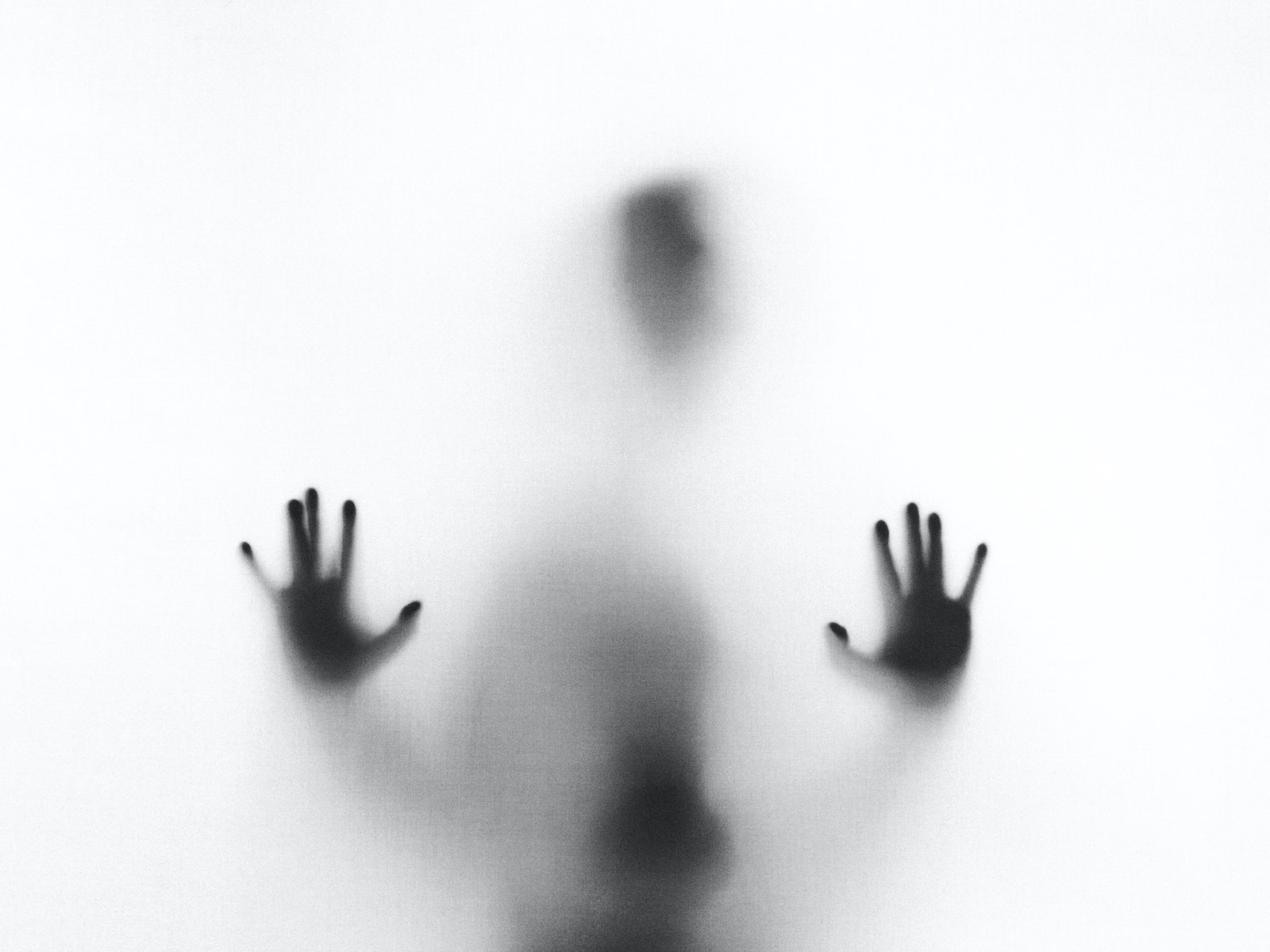

Becca’s thick black hair is frizzy now. She scrapes her fingernails over a piece that has stuck to her cheek and shoves it behind her ear, then wipes her clammy palm on her jeans. She is tired, sticky, and irritable. She leans over Maria, who draws a picture of her family. Maria has mischievous brown eyes and long brown hair that starts the day in a neat braid and ends up wild and unruly. She needs a silver crayon for her grandmother’s hair, and as Becca reaches backwards for the box of crayons in metallic shades, she glimpses a small, unknown boy sitting alone. The child is wedged into a corner in the cubby room, where the children store their light coats and muddy rain boots. A bright green scarf on a hook dangles over the boy’s forehead and his knees are pulled in close so that only his huge round eyes make any impression. Becca has never seen the child before, and his sudden presence, tucked neatly into her cubby room, shocks her. His body is small and shapeless in a bulky coat and dark pants. The skin on his face is an odd grayish-brown.

Becca, composing herself, puts her school smile on, the cheery fake one that crinkles her dark brown eyes and makes her dimples deepen. She stands and walks over to the child. She moves the scarf aside and sees scratches on the child’s forehead that are darker than his skin. She wonders if their color comes from dried blood, and the thought fills her with horror. Her heart begins to beat arrhythmically like a badly-played drum, and her hand flies to the pendant she wears, always, around her neck. She forces her smile wider. In her chirpiest voice she says, “Hi sweetheart, what’s your name?”

The round gray-brown child says nothing. He stares at her.

She hears a scream in the classroom behind her and turns to see Brandon chasing Maria with snot on his finger. “Booger!! Booger!!” he screams, while Maria howls in terror.

“Brandon, stop it!” yells Becca, clenching her fist around the pendant. Brandon falls on the floor, laughing, and then eats the snot. Maria sobs, throwing herself onto the rug and kicking her feet into the air until her corduroy skirt is bunched around her waist.

Becca groans quietly and clenches her jaw. She turns back to the cubby room but the strange gray child is gone. She yanks the green scarf to the side, but all she sees are Brandon’s small, muddy boots. She feels oddly bereft, as if she misses him. Her hand drops to her side, but she doesn’t move away. The green scarf dangles mutely, keeping its secrets.

#

At home that evening, after dinner, Becca’s boyfriend Jim hands her a glass of cheap white wine. They are in their fourth-floor studio apartment on 210th Street, on the big green couch they found on a street corner last month. As he sits down next to her the sofa cushions pop up abruptly, and she grips her glass, annoyed.

“Couldn’t he just be a new kid?” Jim asks. “Sometimes children show up in the middle of the school year, don’t they?”

“Well, of course, but that doesn’t explain how he disappeared. And if he’d been new someone would’ve brought him in and introduced him. Children don’t just show up in a new classroom on their own. And they don’t disappear like little ghosts, either.”

Jim ponders this, his blue eyes drifting to the ceiling. “Maybe he was in the wrong room? Maybe he snuck out. Don’t worry about it, sweetie.” He places his huge hand on her thigh, and it feels so hot and sweaty she jerks her leg before she can stop herself.

“It really doesn’t matter what happened, he’s a child and he needs supervision,” she snaps. She stops, then breathes slowly, feeling guilty.

Jim pulls his hand back, his face turning hard.

“I just mean—I have to find out who he is and who’s looking after him,” Becca continues. “And why there are scratches on his face. What if he’s not safe at home? This is a child, Jim. I’m responsible for him.”

Jim takes a sip of his wine and grimaces. “Sure. Yeah, of course.” He pulls his phone out of his pocket and begins tapping at it.

Becca sighs, knowing they’ll be strangers the rest of the evening. Her eyes begin to smart and she blinks, hard. Outside, an ambulance siren begins to blare. She sips her wine and thinks about the child.

Later that night, after they’ve gone to bed with a cold kiss goodnight, Becca wakes up with her stomach convulsing. The pain is so bad she can’t make a sound. No, no, not again, she thinks. She feels the bile rise in her throat and leans over just in time to vomit, loudly, into the empty plastic trash can she keeps next to the bed. She allows the hot acidic spit to drip out of her mouth and then wipes her lips hard with a tissue. There is a little vomit in her hair, yellow against black, and she cleans it off carefully. She looks over at Jim, who snores peacefully. Vomiting alone while he sleeps, she thinks, and bites her lip. She swings her feet to the floor and tiptoes to the bathroom carrying the white can, liquid sloshing at the bottom as the smell of cheap white wine drifts upwards.

#

The next day there is a doctor’s appointment, early, before school. Becca has waited six weeks to meet with Dr. Kaufman in Murray Hill on the east side, who she has chosen because he is in her insurance network. She waits in a large dark lobby with brown leather chairs. Please let him help me, she thinks as the nurse leads her into a small office with yellow walls. She is hopeful but nervous. The doctor has a tired, kind face, with deep wrinkles and long nose hairs. He reads her intake papers quietly while she waits. She imagines trimming his nose hairs and the thought soothes her. Finally he looks up. “When did this start?” he asks.

“About five months ago,” she says. “Give or take a bit.” She presses her lips in and does a little bopping movement with her head, side to side, to show the unknowable nature of time passing.

“Hmm,” he offers. “Any chance you were sick around then? Flu, maybe? Even a period of high stress, perhaps?”

She hesitates. “Oh,” she says, and stops. She feels faint. “I don’t think it’s connected but—” She rubs her necklace between her thumb and forefinger, then presses the edge of the pendant into her cuticle, hard. “I was pregnant. I was—. For four months. I was pregnant.” Her voice feels too loud and she clamps her mouth shut.

“And…” His eyes dart to the right and back to her uncertainly. “What happened to the fetus?”

“I lost it. I mean—I had a miscarriage.” Her brain floods quickly with memories: the two pink lines; the ultrasound, with its fluttering heartbeat, like the wings of a hummingbird; the young doctor, slick-haired and glamorous in stilettos and a white lab coat, peering wordlessly at the screen; Jim’s eyes, curious, only mildly disappointed. She remembers—can feel it now—that awful week, waiting for surgery, carrying the poor dead creature back and forth to school—thinking, there’s death in me. Then, the night before the surgery, lying awake, pleading, Don’t take him from me, don’t take him—she made him male although the baby hadn’t developed enough for a gender. Wretched as she was, she prayed for that night to last forever, so that she could stay his mother. Finally, in the hospital the next morning, the surgeon casually dropping a cardboard box, like a take-out container, on the bed. HUMAN WASTE SPECIMEN, it read.

“So, five months ago you lost the fetus?”

Becca inhales sharply and looks up at the doctor. His nose hairs flutter gently as he breathes. She is back in the bright yellow room. “Yes, that’s right,” she says. Her hands shake and she clutches them hard.

“It’s terribly stressful,” the doctor says. “What you’ve been through has left your body reeling. Not just emotionally, but in a very real, physical way, too.”

Becca blinks, her breath quickens. She shakes her head. “No,” she says. “How can it be just that? It’s too much. The vomiting, the pain. There’s something wrong with me.”

He looks at her so intently and for so long that she begins to wonder if she’s done something shocking and forgotten. “What went wrong?” he asks softly.

She pushes her cuticle into the edge of her necklace again, and focuses on the sharpness of the metal in her flesh. Chai, in Hebrew lettering, the rectangular hay with three walls, and the tiny vowel beside it, an apostrophe. Life. The necklace was a gift to herself, much too expensive, one lonely day in the Columbus Circle mall, a week after the surgery. She says, “Just a chromosomal abnormality,” articulating the difficult words carefully. She shrugs.

“Becca,” he says, and she looks at him. “It was never meant to be a baby. It could never have survived. Happens all the time.”

She examines her cuticle, which has developed a hard gray callus, and purses her lips in affected concentration, as if the cuticle is very interesting. Her cheek twitches. It was never meant to be a baby; she repeats to herself. What was it then? She glances up at him and sees his eyebrows pulled in tight. He’s afraid I’ll cry, she thinks. She will have to put him at ease. Suddenly she hates him.

She smiles. “That’s true,” she says. “Wasn’t meant to be, I guess.”

He smiles, relieved. “Let’s do an endoscopy. Get in there and look around.”

She nods. She is hopeful again. “Okay, when?”

“Tomorrow morning?”

It’s Friday and there is no school tomorrow morning. “Yes, please,” she says.

#

Out on the street she walks towards the 6 train at 33rd Street. She will have to take it down to 14th, then the L across town, then the A uptown to 175th. On a good day it’s an hour, and it’s never a good day in New York. As she hurries to the subway she avoids eye contact with the frowning men and women in suits who rush by. She hates this part of town; it has the cold feel of money, and is nothing like the vibrant city in which she and her friends live and work. She’s thinking this when she spots a gray blur huddled in the freight doorway next to a large office building. It is the strange child with the scratches on its forehead. She stops, her breath catching in her throat. She stares at the child. He looks back at her with great big mournful saucer eyes. His knees are pulled up to his chest but in his baggy pants they seem to have no bones in them. He seems larger than the day before. He wears the same shapeless coat he wore in the schoolroom. He is so totally without edges he could be made of mud. His body and skin make no sense; there is something inhuman about him that terrifies her. And why is he here? Is he following her? She looks in his dark eyes, which seem full of expectation, as if there is something she must do. “What do you want?” she asks.

He stares at her wordlessly, and then opens his mouth. Becca sees that it is completely black inside. Jesus, where are its teeth? she thinks.

His mouth stays open but he says nothing. Becca’s hands shake; she opens her backpack, fumbles with the zipper, and pulls out her wallet. She grabs all her cash, twenty-three dollars, and holds it out to him, but he doesn’t move. She stares at him, breathing hard, and then drops the money at his feet and takes off, running. By the time she reaches the subway steps, purple spots cloud her vision. Her head feels like a balloon floating above her body. Once she is through the turnstile, she reaches for the wall and slides down until she is sitting on the filthy platform floor, gasping.

#

The next day Becca is at the hospital at 8 am, sitting at a desk in the check-in area. The woman behind the desk tells her that they can’t do the procedure unless she has someone there to drive her home. “To drive?” she asks, then breaks into a loud laugh. “This is New York. I don’t even know anyone with a car.”

“Well that’s our policy, ma’am. We can’t put you under unless you have someone to drive you home.”

Becca looks around, wanting to share this uniquely New York joke, but everyone else is focused on their own sickness. She sighs, still smiling slightly. “Can I do it without going under?”

The woman’s eyes widen. “Well…technically yes, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone do it.”

“I’ll do it.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes. Let’s just do this.”

#

An hour later the long tube has been pulled up through her GI tract and out of her throat and she’s dressed and seated in another chair in front of another desk.

“Well, you have severe inflammation,” the doctor tells her, “but I can find no root cause.”

She exhales sharply. “Ok, so what do we next?”

“You live your life. Figure out what your triggers are and just don’t eat them.”

“That’s it?”

“Yep, that’s it. Try an elimination diet,” he says cheerfully, beginning to rise.

“No,” Becca says, and stops herself. She breathes out sharply.

“No?” the doctor asks, confused. He sits down. “You don’t want to try the diet?”

“No, that’s fine, I’ll try the diet, but…isn’t there anything else we can do?”

The doctor sighs, then smiles at her kindly. “We’ll run some blood tests,” he says.

Becca hesitates, sensing his irritation. “I don’t want to put you out,” she stumbles.

“It’s no trouble,” he says, glancing at his watch. “Let’s take a look at your labs and see what we find. I’ll order some tests, and you can take it to the Quest Labs on 207th when you get a chance, alright? Just take a seat outside and I’ll be right out with the testing order,” he offers, standing up again to usher her out of the room.

#

Walking up Broadway to the A train she is lost in her thoughts when she sees the child standing next to an old phone booth. Except now he’s huge. He must be eight feet tall, towering above the graffiti-ed booth. He stares at her hungrily with those same big, haunting black eyes like perfect dark circles; black holes of yearning in a round gray face. She stops, immobilized with fear. He is the ugliest thing Becca has ever seen. He is not human at all, more like an enormous turtle with no shell. He has deep black cuts in his forehead and a mouth that is a gaping, jagged hole, as if it were carved out messily with a dull knife. His body is an amorphous mush of limbs and flesh, no bone or muscle at all, and yet Becca feels that he is terribly strong and could destroy her.

Becca’s heart races, her mouth is open, her throat goes dry. She looks around for help but realizes that no one else is looking at the creature. No one else seems to find this giant puddle of flesh exceptional or surprising. She is shaking. Her heart bangs against her ribcage and she feels a giant scream collect in her diaphragm, like a taut wire coiled around a spring. When it finally spins out, it goes so fast that the end of the wire seems to snap against her brain and she falls to the ground, screaming.

#

It is one week since Becca’s panic attack. All week she has been jumpy at school, snapping at the children and then apologizing guiltily, placating them with sugary treats and hugs so long they squirm to wriggle free. Wednesday she kissed Maria’s cheek just as the vice-principal, Mrs. James, glanced through the window in the classroom door. Becca has been in a frenzy of guilt and worry ever since, although no one at work has spoken to her about it. Between her terror of the child-giant and her fear of being fired or shamed by Mrs. James she has been unable to sleep or eat. Without food she’s been spared the vomiting and stomach cramps, and so has spent her nights on the green sofa, reality shows playing on her laptop while her mind wanders, glancing at the windows periodically as if the child-giant will appear suddenly outside her fourth-floor apartment like King Kong stalking Faye Wray.

On Monday, Becca waits in the lobby of the Quest Labs blood testing facility on Broadway and 207th Street. Outside the window the scaffolding dims the sunlight, darkening the faces of the people walking by. The room is brightly lit, with identical beige chairs arranged in rows. Becca sits in the chair closest to the wall, clutching the doctor’s request. She studies it as though the names of the tests themselves will finally illuminate her condition, spill the secret her body keeps. “TTG IgA antibody test” she reads, and shakes her head, sighing sharply. She looks up at the television mounted in the corner, where a rerun of Judge Judy plays. “It’s time to grow up!” Judy yells at the sheepish man behind the podium. “Get a job and take care of your damn kids!”

From the inner room of the testing facility comes a scream so loud and sharp that Becca’s entire body goes as taut as a tightrope. She stands up abruptly, her breath coming quick and hard. The doctor’s lab request flutters to the floor. There is another shriek of pain, high-pitched, desperate, too nasal to be coming from an adult. Becca steps quietly into the hallway. There is only one door, on the right, standing open. Becca creeps to the doorframe and peeks into the room. Inside is a young couple holding an infant. A woman in a white lab coat, her hair in a tight gray bun at the bottom of her head, holds a large syringe, the needle deep inside the baby’s inner elbow. The baby is so tiny that the tube coming out is as long as its arm. The phlebotomist is slowly pulling back on the stopper as the clear tube fills with blood. The baby is howling wildly and the mother murmurs in low tones, her blonde hair falling over the baby’s face.

Panic begins to grow in the pit of Becca stomach. She breathes quickly, and her lips and throat twitch with fear. She looks down at her hands, which shake. She feels herself incredibly tall in the room, as if she has doubled in size and will crash through the ceiling like Alice in Wonderland. Why would they need blood from an infant? she thinks. Her eyes begin to itch and she shuts them hard to keep the tears in. The baby lets out another, piercing scream and Becca’s eyes fly open. The syringe has filled with dark red blood. The attendant pops out the clear plastic tube and attaches a new one to the needle, still lodged in the baby’s arm. Becca can see where the needle pushes up the baby’s skin like a long stiff worm eating into its flesh. These people are torturers, she thinks. She is sweating, she can’t get enough air, and her mouth has gone dry. It occurs to her that she will die from fear. I have to get out of here, I can’t watch this, she thinks. She runs to the door, leaving her bag on the chair in the corner. She gasps for air in big hungry gulps and the tears have broken through.

Outside on 207th Street there is scaffolding between her and the street, and a rush of people on either side of her. She is trapped and can’t find her way out. She sobs as she turns to her left, pushing through the passersby, wailing like an animal in a trap. She clutches her necklace, pulling it against the back of her neck as if she could slice right through. Finally she spies a gap in the thin metal poles and she runs to it, stopping just at the curb. The morning light is so bright she has to shut her eyes for a moment. When she blinks them open he is there, her child-giant, towering over the city buildings like Godzilla. She cranes her head, and her mouth drops open at his enormity. Her eyes travel up his body until she finds his dark black eyes gazing down at her. The flesh below them shimmers like rain on pavement. Is he crying for me? she wonders. He seems to be expanding as she watches. He has completely blocked out the sun. Everywhere she looks there is only him. The cacophony of cars honking and rushing by her quiets, and as she looks into his eyes, a realization begins to spark and she gasps in recognition. “You?” she asks, and the edges of the monster’s eyes begin to turn upwards into a smile. They gaze at each other. Her boy. Her face softens.

The sound of the cars comes crashing back, but Becca can see nothing in the dark of the monster’s massive shadow. She gazes up at his face. You’re mine, she thinks, and the monster’s eye slashes crinkle even more, as if she’d spoken it aloud. Becca smiles up at him, her body filling with warmth. She steps off the curb and into the street. She hears the car horns blaring and voices shouting but she doesn’t care. All that matters now is that she touch him, smell his skin, kiss him, hear his laughter, dry the tears that make his gray face shine. “And I’m yours!” she cries, as loud as she can. She reaches her arm out to touch him. There is a screech, and a tremendous force hits her and sends her flying. Where am I going? she wonders, and then, This is what being born must feel like.

#

She blinks her eyes open. She is in a rocking chair in a spacious room with white walls. Across from her is a single window, from which early morning sunlight creeps into the room. She looks around but can see only dark shapes against the white. “Hello?” she calls out, and waits for an answer, but nothing happens. The light grows brighter, filling up the room. By the window she sees a metal stool, a long white table with specks of gray on it, and a large lump of clay on top. Next to it is a small wooden knife. None of this makes any sense to her, but she isn’t worried. She feels happy, light, curious. The curved wooden arms of the chair are smooth and cool beneath her hands and she inhales deeply, fully.

The light from the window grows brighter, illuminating the room. She feels a movement on her lap and looks down. He is there, her quivering, misshapen creature, but now he is so small he can fit in two of her hands held together with the pinkies touching. He reaches his little monster arms up to her and whimpers. She stares at him, her breath quickening, her eyes running up and down his body. He is like a little fish that’s been chewed up and spit out. She lifts him to her face, pressing her mouth against the lumpy flesh between his arms and legs. He smells earthy, dark, warm, a bit sour. His little heart beats like mad against her cheek. She pulls her head back and gazes at him. His dark empty mouth curls upwards at the edges and his round black eyes squint into happy little horizontal slashes. She exhales softly, deeply, and smiles. “My love,” she murmurs, and leans in to kiss his face.

Victoria Mack is a teacher, actor, director and writer who spends half the year as a Professor of Performing Arts at the Savannah College of Art and Design in Savannah, GA, and the other half writing, acting and directing at home in New York City. She has an MFA from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and a BA from Barnard College. Victoria has been published in Flash Fiction Magazine and Literary Vegan, received an honorable mention for the 2019 WOW Women On Writing Prize, and was shortlisted for the 2021 Able Muse Write Prize. Read more about her at victoriamackcreative.com.

Victoria Mack is a teacher, actor, director and writer who spends half the year as a Professor of Performing Arts at the Savannah College of Art and Design in Savannah, GA, and the other half writing, acting and directing at home in New York City. She has an MFA from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and a BA from Barnard College. Victoria has been published in Flash Fiction Magazine and Literary Vegan, received an honorable mention for the 2019 WOW Women On Writing Prize, and was shortlisted for the 2021 Able Muse Write Prize. Read more about her at victoriamackcreative.com.