The intersection of body and place dominates Natalie Scenters-Zapico’s second collection Lima::Limon, a book that makes explicit the ways in which female bodies are excavated and mined. She writes in “The Hunt,” the final poem of the collection, “I am a lucky / hembra: I have a language / to write of the violence of machos,” and that is exactly what she does throughout Lima::Limon, continuously using language to explore the violent treatment of women’s bodies and her own ability to use that body to create instead of destroy. Not only in the final poem, but throughout the entire collection, Scenters-Zapico refers to her ability to write as an antidote to the bleak landscape of domestic and sexual violence. She writes in the final stanzas of “My Gift:”

I wanted to see if I could mine my body for rubies

& look, I can! I write a letter & don’t send it:

Here is a book & a ruby. One from my body,

the other I made after a fit with a pen. Both

worth nothing, but I like the thought of a man

picking them up & holding them in his hands.

Scenters-Zapico’s book is a gift, her poems rubies, glistening gems that called to me again and again as a reader, as a writer, and as a woman despite her admission or fear that they are “worth nothing”. She has mined her body and created from the observations of the violence done to it, a beautiful examination at the things it — and she — can do in response, can compose and reconstruct. That reconstruction within her work feels important and urgent and becomes even more important and urgent through the connections she makes between body and place.

Scenters-Zapico first makes the direct comparison between women’s bodies and place in the poems “Discovery” and “I Didn’t Know You Could Buy.” In the latter, Scenters-Zapico compares the process of attempting to buy a home that’s not for sale to men who imagine women’s bodies as also potentially up for the taking, despite the signs, the indications she gives, that she is not interested or available. In the final stanzas of the poem, Scenters-Zapico makes her comparison explicit, writing:

My landscape of curves & edges

that breaks light spectral

is not for sale, but men still knock

on rib after rib, stalking that perfect house —

the perfect shade of blue.

What I perhaps admire most about Lima::Limon as a whole is that it makes comparisons like this so directly — there is no hiding from the violence done to women and no hiding either from the effects of that violence on the women who endure it. As she closes the poem, Scenters-Zapico allows her speaker to declare boldly and directly that her body, “her landscape of curves & edges,” is “not for sale”. While this declaration is in some ways futile — the men “still knock” — she gives her speaker agency to make the declaration, to begin to use her voice to combat the violence done to her. By imagining her body as a house, as a landscape, as a country, Scenters-Zapico’s speaker brings up ideas of ownership and boundaries associated with land, property, and borders. This makes the body both somehow more physical (how can a body be more physical? I didn’t know until I’d read this collection) and also at once opens up the violence to include that of colonialism, of the violations of other kinds of sovereign land.

Later in the collection in the poem “Notes on My Present: A Contrapuntal,” Scenters-Zapico furthers this connection between the violence done to women and the violence of colonialism and empire by splitting the poem between her own words and direct quotes from Donald Trump about Mexico and its people. In this way, Scenters’-Zapico becomes explicitly political, connecting the personal violent relationships she’s explored with the violence of society at large. She opens “Notes of My Present” by again comparing the body of her speaker to physical landscape:

I write my body as border between

We have some bad hombres here

this rock & the absence of water.

Here Scenters-Zapico literally interrupts her body-land comparisons with Trump’s words, creating an additional border between the two voices in the poem while also explicitly introducing the idea of her speaker’s ability to create (“I write”). “Notes on My Present” goes on to directly address the idea of empire, declaring in the speaker’s half of the poem, “Macho, you / breathe bright in the neocolony, / a problem of Empire pulling / the capitalist threads of my border”. While the border still belongs to the speaker’s body — the issue at hand is still largely the Macho’s violation of the speaker — the border here, given the references to colony and Empire, also begins to take on geographic and societal meanings. These double kinds of borders then — and the multiple ways men can violate them — both expand Scenters-Zapico’s concerns beyond sexual and domestic violence and also enhance it. Women’s bodies are as big, as important, and as rightfully independent as bodies of land and in tying together those two kinds of violent border crossings, Scenters-Zapico casts a broad and angry censure with a speaker at the center who is capable of exposing that violence, whose voice — “I write” —- creates the lens through which to see it.

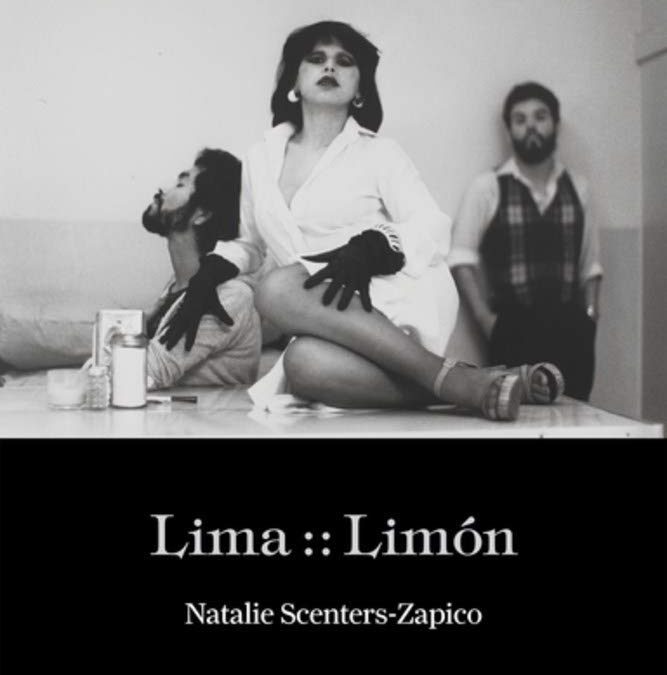

* Works Cited — Lima::Limon. Natalie Scenters-Zapico. Copper Canyon Press, 2019