Reviewed by Lindsey Grudnicki

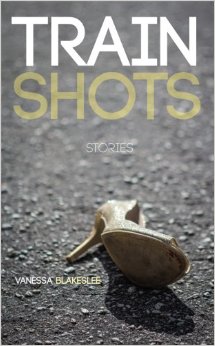

In her debut collection of short fiction, Vanessa Blakeslee offers a frank look at the defining trials – from the small inconveniences to the traumatic, inescapable events – of human life. Through eleven skillfully-written portraits, she takes readers to the pinnacle moments of explosive situations, when her characters face either destruction or renewal of mind, body, and heart depending upon their next move. Her stories read as ballads of brokenness, chronicling the strife, anger, guilt, disappointment, and disillusionment that all of us face.

Blakeslee’s range, both stylistically and in her talent to craft a unique narrative voice, is impressive. Her collection first pulls you in with the fast-paced monologue of a restaurant employee training a new-hire (“Clock In”), leaving you as breathless and nervous as the new staff. From there, she takes you into a tormented marriage that has left a husband seeking answers from a Magic-8-like doll (“Ask Jesus”) and later brings you into the orbit of two other couples that, when circumstances cause them to question the foundation of their relationships, must struggle to find happiness together or choose to let go (“The Lung” and “The Sponge Diver”).

The book shifts gears in “Welcome, Lost Dogs” as a “gringa” in Costa Rica reflects on the loss of love and home after her adopted dogs are stolen. Near the conclusion of the piece, the woman muses that “there are three kinds of grief: the grief of the definite, for what once was and is now gone; the grief of the indefinite, where there are no answers and so the worst is suspected; and the grief of the inevitable, for what must be lost and whose future must be abandoned.” These categories of devastation run through a number of the remaining stories. From the “grief of the definite” that a young single mother must overcome in order to find her footing in “Uninvited Guests,” to the “grief of the indefinite” that plagues a suicidal celebrity in “Princess of Pop,” Train Shots explores the depths of heartache and investigates how men and women muddle through the pain – that is, if they are able to.

While all of the works in this collection are powerful and polished, there were two that, to me, where simply haunting. In “Barbecue Rabbit,” Blakeslee throws readers into the tense relationship between a mother and her violent, emotionally-disturbed son. As both teeter on the brink of sanity, the undercurrents of fear and hatred evolve into a tidal wave that leaves a vivid, utterly terrifying final scene in its wake. We see “the grief of the inevitable” in this tale as well as in the collection’s namesake, “Train Shots.” After a girl kills herself by jumping in front of his train, a middle-aged engineer must cope with the oppressive sense of guilt and loss that lingers after an incident that, while beyond his control and understanding, troubles his conscience.

With its memorable characters, simmering locales, complex relationships, and mounting intensity, Train Shots leaves quite an impression. Both ordinary and extraordinary lives are put under Blakeslee’s microscope, and her writing is at times stark and unsympathetic, often compassionate, and always authentic. She is certainly a writer to watch, and the strength of her first book promises great things.

Train Shots will be available from Burrow Press in March 2014. In the meantime, check out Vanessa’s website (http://www.vanessablakeslee.com/Products.html) to read more about her work.