I grew up in the south end of Seattle during the seventies. My childhood home was on 38th street, a block made up of Black families, a Filipino family and two white families – mine being one of them. 38th street sat on the impoverished edge of Mt. Baker’s wealthiest neighborhood. Our parents were blue-collar workers – janitors, cooks, mechanics, seamstresses, and steel workers. My Dad worked swing-shift at Kenworth and my Mom worked in a garment factory in Bellevue.

There were about twenty-five kids on 38th street, mostly from large, latch-key households. After school we spent every drop of daylight together unsupervised. We were a scrappy lot. We stole shopping-carts from the IGA grocery store and made trick go-carts. We had rooftop pine-cone wars. We fashioned rickety ramps from milk cartons and did Evil-Knevil jumps on our banana-seat bikes. We played bloody games of touch football, naughty games of hide-and-go-get-it where boys kissed found girls, and high-stakes games of spades, craps and spin-the-bottle. We sat for hours on Big Mama’s stoop cracking jokes, listening to jams on the boom-box and watching little Nate break dance, until our parents called for supper or bedtime or a round of scolding.

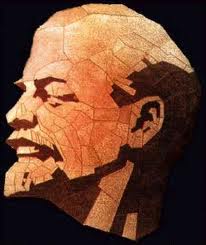

It really didn’t seem to matter that I was white. What did matter was that my parents were members of the Revolutionary Communist Party. My Mom and Dad were singularly devoted to the RCP – and our house was Party central. RCP members came in droves to our living room and stayed all night to chain smoke and sip Yuban coffee and Olympia beer. They talked with their hands and spent hours debating the collected works of Mao, Lenin, Stalin and Marx. They talked in whispers and used code names. On Thanksgiving they hunkered down at our dining room table and ate holiday ham.

I lived a double life. I was a tomboy on 38th street and a protégé in the Revolutionary Communist Youth Brigade. I shared food, homes, and clothing with the other commie kids camped out at Centro de La Raza, Revolution Books, and the Worker Center. After school my little sister and I would get off the Metro bus at Winchell’s, buy two donut holes and slip next door to the Worker Center hoping none of our school friends saw us.

I was conflicted about my Mom and the Party. I hated how she held my friends hostage in the living room and lectured about the war-mongering U.S. government. I hated that she was oblivious to the numbing affects her rhetoric and red flag-waiving had on people. I hated needing to escape her politics and the chaos in my home. I hated seeking asylum in other peoples’ homes with cockroaches, horny brothers, creepy stepfathers, and terrifying schizophrenic aunts. I hated having to explain to nervous teachers and friends’ parents that communism was about helping poor people, ending police brutality, stopping World War 3, and rewriting history books.

My Mom’s approach to education made up for much of this animosity. She railed against the lies we were taught in school and shared radical ideas with our teachers about slavery, women and war. She challenged them to burn the textbooks and replace them with copies of Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States. She wrote blanket notes excusing us from class when there was political work to be done. Once I missed a whole week of sixth grade to attend Joe Hubert’s police shooting inquest. I sat beside the slain boy’s stoic mother, Mrs. Hubert, who squeezed my hand and told me I should be proud of my Mama. I was proud of her when we storm-trooped Mayfair during the farm-worker’s boycott against grapes. I was proud when she sent me and a teenage Youth Brigader on the Greyhound bus to LA to attend Mao’s memorial service. I was proud when we held hands and sang the ‘The International’. On the last chorus we pumped our fists in the air and tears fell from her beautiful green eyes. I cried, too.

My mom, the magician. She transformed gun battles between rival gangs into articles about the oppressed seizing their future. I clamored on top of the light board and carefully trimmed her words to fit the front page of the next Revolutionary Worker. I imagined carrying a gun, mass bloodshed, and the oppressed breaking free from their chains. These salty fantasies were steeped in typesetting ink and the hypnotic hum of the printing press and left me weak in the knees. Lying on the green shag carpet under my Mom’s desk I imagined my little sister hiding out in the Klickitat fort, surviving on a tin of Spam while I forged a burning path. I returned to reality dreading the hours I would have to spend with my Dad and comrades agitating the masses, trying to hawk the Revolutionary Worker at the Pike Place Market, Yesler Terrace housing project, and my school.

At night I studied the Revolutionary Worker and looked up the countless words I didn’t know. I sat on the plaid couch opposite my Mom’s recliner and pored over the gold-leaf pages of our huge Randolph House dictionary. I remember searching for the word homosexual. The headline read, Stalin Denounces Homosexuals. I wasn’t sure why Stalin would denounce homosexuals but I knew that the kids on 38th street hated homosexuals – or homos, as we called them. I learned from the dictionary that a homosexual is someone who has sexual desire towards someone of the same sex. Stalin viewed homosexuals as criminals who suffered from the obsessive spoils of capitalism. After the Russian revolution he outlawed homosexuality as an ugly stain left by Western culture.

The dictionary definition explained why we called the boys homos if they played touch football and made too many tackles or spent too much on the pig pile or chased after other boys a little too intensely. It explained why we called Michael Jackson and Dennis Vandlanderham homos. Dennis lived two blocks above 38th street in a stone mansion. He and Michael Jackson showed their desire for boys by wearing tight jeans and talking and acting girly. I hated Dennis Vandlanderham for being a snitch. I hated his thin red hair and tiny fishhook nose and high-whiny voice. I hated that he threw lefty and wore pointy red Mr. Roger shoes. Stalin’s principal of homosexuality made me hate Dennis Vandlanderham in a new light. He was worse than a snitch, he was a degenerate side-effect of capitalism whose reactionary tendencies were likely to spread. Dennis Vandlanderham must face the wrath of the working class.

I decided to follow Dennis home after school and teach him an important lesson. I counted each one of his bouncy steps in an effort to collect data and glean courage. When he got to his lawn’s edge I raced up behind him. He turned and smiled when he realized it was me. We both seemed small standing beside the granite boulders lining his walkway. I wanted to reach out and touch the gleaming brass knob in the middle of his door but the smell of beauty bark made my nose twitch and reminded me of my political mission. Pressing on my toes I got right in Dennis’ face. I smelled the minty wad of gum in his mouth. “You think that being rich means you can get away with being a homo – well think again.” I flung the words with a burst of anger and they landed in a strand of spittle on Dennis’ freckled cheek. I heaved my right arm and felt my fist smack against his jawbone. Dennis stood completely limp, making no attempt at a verbal or physical exchange. His bottom lip started to quiver and his pale blue eyes turned liquid. He uttered a strange wet sound and disappeared behind his magnificent front door.

Every time I replay that scene waves of shame crash against my belly. I was the brave revolutionary who confronted a revisionist homosexual. I was the pathetic poor kid who envied the privileged white kid. I was the tomboy on 38th street and the protégé in the Revolutionary Communist Youth Brigade who never told anyone about my attack on Dennis Vandlanderham.

I watched Michael Jackson transform from a young show-stopper into an awkward man-child. With each bizarre identity twist a familiar wave of shame fell over me. Michael’s silken voice turned squeaky, his beautiful face became a graveyard, his caramel skin turned ashen, and his proud afro melted into gluey strands. No matter what he did, Michael Jackson couldn’t undo his true nature anymore than I could undo my true reason for revolting against Dennis Vandlanderham: I was a child. I never wanted to be gay.