On a rainy afternoon in the spring of 2011, my five-year-old son dumped a heavy book into my lap and said, “Read.” I opened the book and read the first line: “All children, except one, grow up.” The book was Peter Pan and Wendy, by J.M. Barrie, first published in 1904, and the sentence was alarming. My older son joined us on the couch. I kept reading, but I felt scared. I think the boys did, too.

A few weeks later, on Mother’s Day, I sat alone in a coffee shop with a notebook and surprised myself. I started drafting a poem about a bitter, working-class Neverland fairy angry at her weak body, and at times overwhelmed by desire. (This is less a departure from the J.M. Barrie story than you might suspect; if you’re picturing Disney’s tiny gold light with fluttery wings, I suggest you check out the book.) The poem, “Tinker Bell Thinks About What She Wants,” was about Peter Pan, but it wasn’t for children. When I finished it, I could tell I wasn’t done.

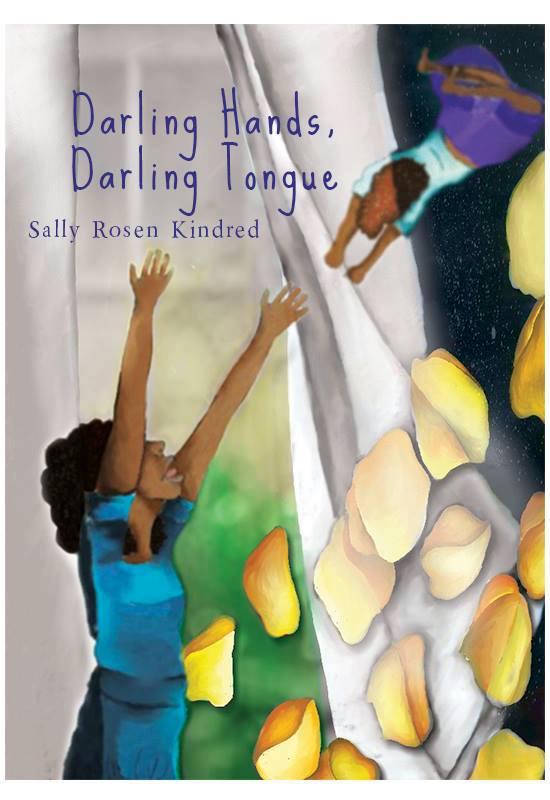

After that I spent a year writing poems about Wendy Darling and Tiger Lily, childhood and motherhood through the lens of Neverland—poems about Lost Boys and Lost Girls. And more Tink poems, of course. (My friend Nancy, who is the kind of person you want to talk to endlessly about motherhood and Peter Pan, still calls the project “the Tink poems,” and so do I.) I wrote about girls’ actual voices and bodies, about how we are written and told by others—the stories that free and ensnare us. Those poems became a chapbook, Darling Hands, Darling Tongue, released last week by Hyacinth Girl Press.

“All children, except one, grow up.” It sounded to me like dangerous information. It sounded like giving away the goods. I loved that it scared me, as a mother, to read this story to my sons. I loved that I was as thrilled as they were to escape from Mother and Father and fly off to Neverland. The island itself began as a story Wendy Darling told—her wish, her wish come true, that took her from her last life. The new story promised her forever childhood, but also took it away, because it removed her from the parents who made her a child. Stories are dangerous things, and so is growing up.

I loved, too, the promise my poems made that the girls—Tink, Wendy, and Tiger Lily—would have a strange new chance to speak about how hard it was to be girls in girls’ bodies, in a boy’s story, with its fists, hooks, and oceans. Wendy could fly to Neverland, but when she got there, she had to be a mother to her brothers and the Lost Boys. Tinker Bell could experience desire—for autonomy, and for Peter–but she could not be fulfilled, since Peter and his world refused to grow up. She could not get outside the small fairy body that has to be clapped back to life by boys who must believe in her for her to live. In this way, she was like so many girls I knew. As a story that needs boys to tell her, how long could she possibly last? And then there’s Tiger Lily, who is not white, and does not get to speak at all. The poems needed to hear these girls, to give them the page.

So that’s how I spent a year with a stack of spiral notebooks and a copy of Peter Pan. It’s how I ended up teary-eyed in a Dunkin Donuts, writing an autopsy report for a fairy. (She couldn’t possibly die in Barrie’s story; she couldn’t possibly survive mine.) And it’s how I began to teach my boys to leave me—to listen to me, and to stop listening—and gave them a lap, a couch, and perhaps the wrong story to fly from. Like the Lost Girls, my sons needed to be heard, and we all asked a lot of questions about the book. We told our own stories, especially the scary ones. We continue to embrace stories, though by the chapbook’s end, Wendy Darling would like to let them go. In the final poem, she imagines her own tale going another way:

I think now I was meant to be the clock

in the crocodile, to claim warm minutes

in the story’s gut,

in the boneless dark

alone, and later,

with Hook beside me—

a kind of matrimony. We’d

lie together. In that center

I’d stop pretending the world

wasn’t a mess of salt and hunger

winding down. Our words

would taste metallic, breaking

in the acids of desire. We’d be like

my heart, dirty and wild, counting

inside a body

turning away from story,

dipping under the sea.

Sally Rosen Kindred is the author of No Eden (Mayapple Press, 2011). She has received fellowships from the Maryland State Arts Council and the Virginia Center for Creative Arts. Her poems have appeared inQuarterly West, Hunger Mountain, Linebreak, and Verse Daily. Her chapbook of poems, Darling Hands, Darling Tongue, is just out from Hyacinth Girl Press.