Losing Art An excerpt from LOSING ART, a memoir by Patricia Feinman

I got as close to Art as I could, resting one arm on either side of him, without letting any of my weight lean on his emaciated body. I looked into his face. It’s okay, my love, I said. You can go … I’ll be okay. It was a lie. I had no idea if I would survive the loss of him.

Careful to avoid any of the tubes that were attached to him, I lay next to him. Art’s grown daughter Zoë—our daughter now in every way that mattered—crawled onto our marriage bed and positioned herself on his other side. I’ll be okay Dad, she said. You can go.

Art had been in and out of a fitful sleep all day and into the night. He woke up every so often to cry out in fear, or moan in pain. The Fentanyl patch didn’t appear to be doing anything at all—the directions said to apply it to the meaty part of his arm—but cancer had ravaged his flesh and left his body as little more than skin and bone. My alarm was set for every two hours, and I gave him alternating doses of Valium for anxiety, and Hydrocodone for pain. I ground up the pills and mixed them with honey and let them dissolve in his mouth.

Zoë and I got up and moved around, glanced from time to time at the TV screen mounted to the wall, unwatched but on, because it provided a familiar flickering light and muted sound and precluded the need for conversation. The door to the room was open, and as I lay in bed next to Art, I could see his stair chair—static—at its post at the top of the stairs, and suddenly I couldn’t bear to look at the fucking thing any longer. I pressed the button on its arm and walked next to it as it made its slow passage down the stairs, remembering the first time Art had ridden it up to our bedroom—back in the days when we still had hope. Art would never again walk from our bed to the chair and ride it downstairs. We would never again take our twenty-three-minute walk inside the house, Art’s imagined mile. We would never again get in our car and drive to the store or the post office or to chemo. We would never again talk to each other, laugh together, hold each other in the night snuggling deeply, walk down the street holding hands, kiss or make love … Art was dying now—not in some unknowable future moment. We had taught ourselves to live in the moment … but not this fucking moment … in this and every future moment, there would be no Art.

I straddled him again, and I repeated my words—thinking that perhaps he needed my permission to leave this intolerable half-life place.

It’s okay, my love. You can go.

Zoë’s words closely echoed mine.

It’s okay, Dad. You can go.

I’ll be okay.

I’ll be okay.

It was impossible to know if he heard us because he gave no outward sign.

Later, it was sometime around twelve-thirty in the morning—we’d been on this not-deathwatch since early morning, and not paying attention to the arbitrary passing of time—Art suddenly arched his back as he gasped for breath. I put a few drops of liquid Mucinex onto his tongue to help him breathe—it had helped him before—but it seemed as if in his panicked state he had forgotten how to swallow. I kneeled over his body, my elbows resting on the bed, my hands at either side of his head, my face inches from his. Suddenly, his eyes overflowed with fear—and he looked deep, deep, deep into my eyes—as he took one final gasping breath.

It’s over? Zoë and I said to each other as we held our collective breath, waiting for Art to take one last breath. It’s over, we said when that breath didn’t come.

I lay back down next to Art’s body. I don’t want to call anyone to come, I said to Zoë. Not yet. Suddenly, shockingly, Art wasn’t in this body anymore—but this body was all I had.

Okay, she said, and she left the room.

I pulled the long silver chain of his cross over his head, and I put it around my neck. I took the wedding ring off his finger, and I placed it on my middle finger next to my wedding ring—the two rings touched and formed the figure-eight symbol for eternity. I cut the hated catheter with a pair of scissors, and it slipped right out with a little squirt of pee.

I couldn’t believe how much I hurt. Slowly and steadily, a new hollowness began to snake its way inside me to become an integral part of my core.

Finally, Zoë knocked on the door and came back into the room. Maybe we should call someone, she said hesitantly. You really don’t want to sleep next to him and then wake up …

Yeah … okay … you’re right, of course.

I asked Zoë if she would get all the drugs out of the house before we did anything else. There were an awful lot of drugs there—I’d been saving them up just in case Art wanted to end things on his own terms. It’s not that I thought that I would take them—I had, after all, been sober for twenty-four years … but … I had never been in this much pain.

I called Tom, Art’s friend from the funeral home and he answered right away. Tom said he was really sorry, but I had to dial nine-one-one. Not hospice—well, he didn’t know that we were with hospice. Hospice hadn’t told us that we were supposed to call them when Art died and not, under any circumstances, to dial nine-one-one. I input the three numbers into my cell phone, and the next thing I knew, the house was filled with cops.

One police officer pointed to the DNR propped up on my dresser. There it is—that’s okay then, he said to another officer …how many were there? Two upstairs with me, a couple more downstairs with Zoë … Chuck-the-dog was locked in my studio, barking frantically.

What’s okay? I thought to myself. Oh fuck. The DNR. Would they really have tried to resuscitate him if we didn’t have it prominently displayed?

What kind of cancer did he have? a police officer politely asked me.

I thought he was trying to make conversation, but this might well have been my interrogation. Zoë told me later that she had a much more formal interrogation in a police car, sitting in the driveway, and she could see other police officers shining flashlights all around—looking for who the fuck knows what—drugs? Well yeah, drugs—it hadn’t occurred to either one of us that it would be their job to take them away. I can’t imagine that they seriously could have suspected foul play—Art’s skeletal form was a portrait of death from cancer.

Lung cancer, I replied.

The police had no more questions for me, and they let me stay alone in the bedroom with Art while we waited for the coroner to come, which took several hours. At some point I tiptoed downstairs and peeked around the corner to see one of the cops counting and cataloguing the drugs … and then I scooted back upstairs to be with Art. I kissed his lips—his always warm and responsive lips—now cold and unyielding against mine. I breathed in the unseen substance of his death deeply, making it a part of me.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

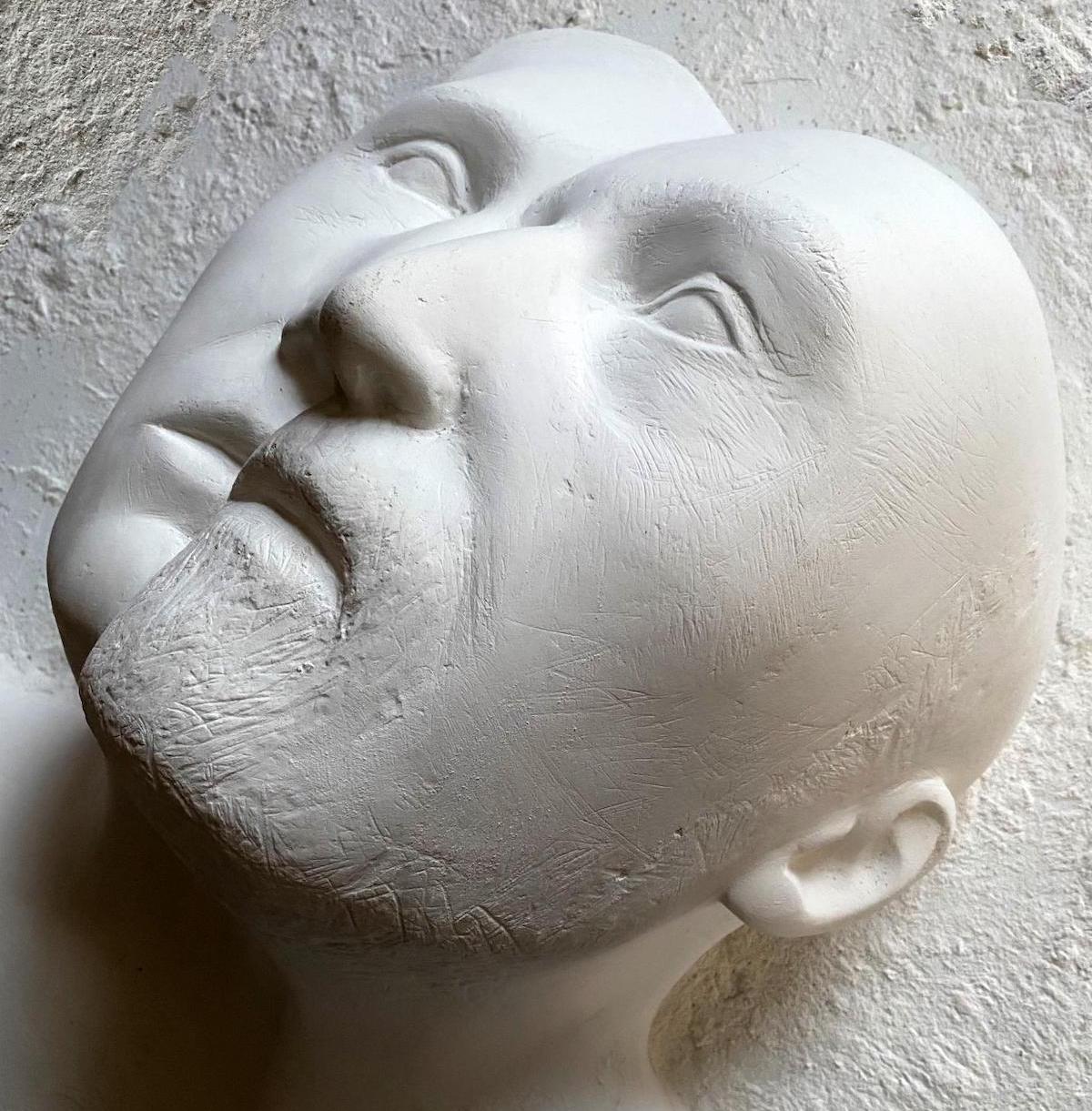

Patricia Feinman is a writer and visual artist. Her sculpture explores the play between the use of universal symbols culled from Greek and Christian mythology and the archetypes of her own unconscious; expressing such themes as: birth, love, sex and death. To see more of Patricia’s work, please visit patriciafeinman.com She lives in the Catskill Mountains with two large dogs. SMOKING WITH ART was just published in the Spring issue of Mayday Magazine and and is currently trending. THE STICK-UP ARTIST will appear in Wilderness House Literary Review. Both pieces are adapted from LOSING ART, a memoir.