Lost Time by Nancy Jorgensen

Two brides in my family never had sex.

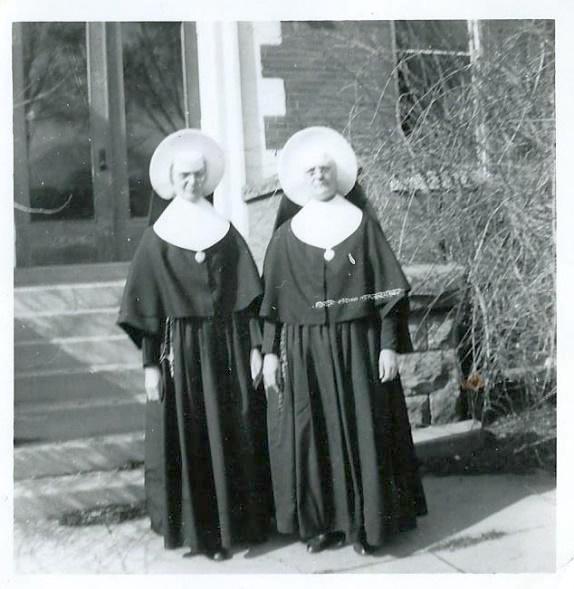

I wasn’t told their birth names. I knew them only as Sister Christine and Sister Hilarion. Born in the 1890s, they wore flowing black tunics, cinched by a coarse rope that dangled a heavy metal cross. A waist-length cape winged their shoulders. Over the cape, a stiff, obedient, white guimpe. Their spotless coif—a fabric covering for forehead, ears, neck, and skull—was topped by a rigid white circle so vast it resembled a spaceship that might orbit them heavenward at

God’s command. They were brides of Christ.

***

I wonder why my great-aunts chose a divine groom instead of a living one. Just like a pimpled, rough-fingered farmer, or a fishy-smelling, black-haired boatman, or a one-armed, onetime soldier, Christ exacted vows. Of faithfulness. Obedience. Labor. But unlike a mortal groom, Christ forbade sexual love.

I also wonder: Did my great-aunts march to the altar, two-by-two, aware of their sacrifice? Or did they wander into a vast unknown, too innocent to comprehend?

***

Since the Middle Ages, some women chose the convent for its status and schooling. A lettered female could be Mother Superior, or Prioress, or Abbess. She could experiment in agriculture, erect buildings, elicit commerce, and oversee properties. But her many subordinates performed manual labor—fingers in dry dirt, hands in soapy water, and forearms in scorching fires. Respite came only when the tower clock rang for prayer. Then the sisters chanted devotions, on their knees seven times each day for lauds, prime, terce, sext, nones, vespers, compline.

***

In her medieval novel, Matrix, Lauren Groff writes of a girl too ugly for marriage. The girl is a financial burden to her family, so they slough her off on the church. The dowry will be less than one for marriage, and the transaction could yield political favor. The young nun eventually rules her convent and plays with ecclesiastical power, politics, and purse. Did someone profit from my great-aunts’ vocations? Were they too ugly and too expensive? Or were they truly devout?

***

I assume my great-aunts grew up like I did, surrounded by adults who revered nuns and priests. Families I knew bred nine or ten children, enough to field a baseball team, and expected one of them to declare a religious vocation. To profess vows. To take one for the team and sacrifice a pop-up fly so all the rest could score.

***

To visit their brother (my Grandpa Pete) in Wisconsin, my great-aunts would have boarded the train in South Bend, Indiana, on break from their teaching duties with Sisters of the Holy Cross. In their soft black carpet bags, a change of undergarments. A crude rye roll and musty-smelling apple. Perhaps two silver dollars, doled out by Mother Superior. A bible. A book of meditations. Rosaries for the children.

***

Grandpa Pete ruled his household and the women in it. So, he was speechless—for the first time, according to my grandma Nana—when his sister/Sister refused to join him in his 1950 Ford sedan.

He had swung open the door and said, “We’re going to the store.” Planted his feet. “Get in.”

Sister Hilarion tucked long fingers under her cape and raised her downcast eyes. She appraised her brother’s broad belly and studied the ultimatum on his face. Accustomed to orders, she prioritized them according to the speaker’s rank. “It is God’s wish. I cannot be alone with a man.”

Grandpa Pete slammed the door, threw his wide backside into the driver’s seat and roared his V8 motor. Gravel dust turned Sister’s lungs heavy. She coughed a few times and then stepped into the kitchen to help Nana pickle beets. Vinegar assaulted her nose, stinging in hot, steamy bursts.

***

It was reported in 2020 that only two hundred U.S. women now enter religious life each year. Total current nuns are down from 180,000 in 1965 to 31,000 today. Many of those are over eighty years of age.

The trend is reflected in my family. Since my great-aunts’ deaths in the 1970s, the women who wed, including me, have all chosen human partners.

***

This year, two of my nephews will marry their girlfriends. The couples are in their thirties, with professional jobs and social awareness. They have purchased homes, lived together, worked at jobs, and explored spirituality.

For wedding gifts, my husband and I made clocks, three feet in diameter, with hand-painted numbers and a sweeping second hand. The pallet-wood planks glow with a patina, earned from exposure to the world. The wood is sturdy and reliable, and any dings or scratches are considered attractive. The clocks are fitted for wall mounting and do not ring or tick. A woman may look at the clock to note the hour. Or she may ignore it and mark life by her own time.

With Grandpa Pete

Sister Christine & Sister Hilarion

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Nancy Jorgensen is a Wisconsin writer and musician. Her memoir, “Go, Gwen, Go: A Family’s Journey to Olympic Gold,” is co-authored with daughter Elizabeth Jorgensen and published by Meyer & Meyer Sport. Her choral education books are published by Hal Leonard Corporation and Heritage Music Press. Other works appear at Ruminate, Prime Number Magazine, River Teeth, Wisconsin Public Radio, CHEAP POP, Brevity blog, and elsewhere. Find out more at NancyJorgensen.weebly.com.