It was snowing when Bess woke and turned off the alarm. She could see large flakes falling in the dim early light. She slipped from the covers and, shivering, pulled on a robe, collected her clothes and opened the bedroom door. It squawked just as it had a few hours earlier when Doug came home from the tavern, but it didn’t awaken him. He lay on his back like a corpse, mouth open, snoring.

Moving quickly, she passed the boys’ room, went downstairs, and lit a cigarette, ignoring the thermostat. It was a waste of fuel to heat the house before the others got up. She boiled water and poured it on a tea bag, then toasted two slices of bread and spread them with margarine while it steeped. There was only a teaspoon of strawberry jam in the pint jar. She considered leaving it for the boys but they’d either fight over it or throw it away, so she scraped what she could off the sides and spread it thinly over one slice of her toast, setting out cereal for the rest of them. God, it was cold.

She washed and dressed in the bathroom, then pressed the switch on the remote starter Doug had bought for her and watched until the car’s exhaust made a steady silver plume in the frosty air. She finished her toast and another cigarette and fastened her boots.

Inside the car a glance in the mirror reminded her that she hadn’t combed her hair. Shit! Oh well, she’d do it when she got to the Rest Home. Ahead of her lay trackless snow, but not deep yet and she knew the road well, each turn and gully. When she got to the paved road, it had been plowed and salted and lay like a grey ribbon through the white wooded land. The only other color in her world was

the dark green of the cedars and pines. Smoking one more cigarette, she passed the lake, the ice not thick enough yet for the fishing huts to claim their stakes.

No one was out and about yet in town. She parked on the street in front of the Rest Home. Willow, her partner on duty for three years now, arrived and parked behind her and they crossed the road together. Through the window they could see the unlit Christmas tree they’d put up in mid-November. Many of the residents were delighted to see it each day, having no memory of seeing it the day before and having no idea how long it would be until the holiday. The first thing Bess did when she entered was plug in the tree lights to brighten the hall.

The night-shift women, Bonnie and Marge, were nowhere to be seen, but most of the residents were up and seated at the table in the dining room. They sat silent, staring at the tables, their heads looking like old dirty piles of snow. Bess and Willow put their coats and boots in the closet beside the door and slipped on their work shoes. While Bess started helping Kathy, the cook, by pouring tea and setting out the right pills at the right places, Willow went down the hall to help with the rousting.

“Well, how are yuz all this mornin’, eh?” Bess boomed to the entire dining room. “Didjuz all see the Christmas tree?” A few nodded wearily. Some looked up inquisitively as she said, “Lucille’s gonna play Christmas carols this afternoon, aren’t ya, Lucille?”

Lucille, a shy woman who said very little but entertained her fellow residents by playing the piano badly every Saturday afternoon, ducked her head.

“What’s that?” asked Billy.

“Lucille’s gonna play Christmas carols today. Two o’clock,” she said even more loudly.

“Oh,” said Billy and left his mouth shaped around the word while he thought about it.

2

Willow came back up the hall pushing Lydia in her wheelchair, followed by Percy doing his shuffle. She said Marge was having trouble getting Louisa up as usual, so Bess went to get her. She had a way of persuading people, an in-your-face cheerfulness that couldn’t be ignored. “Good mornin’ Lou. Everybody’s missin’ ya, sayin’ ‘Where’s Lou this mornin’?’ Come on, don’t disappoint ‘em.”

Finally, following Louisa up the hall to the dining room, Bess waved goodbye to the two departing night workers. As she passed the parlor, she saw no one had fetched Rose for breakfast. Rose was the first one the night girls got up each morning, waking and changing her around six and parking her in the parlor. Instead of dressing her this morning, they’d put a bathrobe on her but hadn’t covered her with a blanket, and she was curled up in her chair, her bare legs pressed tight together.

Saturdays meant residents could come up to breakfast in their robes if they were due to be showered. Very few showered willingly. Some would obediently give in and take one when you reminded them, but the majority protested loudly. This was the morning when Bess and Willow bathed the ones who couldn’t bathe themselves so they’d smell clean for relatives coming to visit on the weekend or for the worship service on Sunday. It was a long process and Bess and Willow wanted breakfast over quickly.

Bess went in and touched Rose’s head gently. The ancient woman had been a resident since Bess had begun working here eight years ago, but in the past couple of years Rose had become helpless. No one could understand what she said if she spoke. “Rose? Time for breakfast.” Bess found a small blanket in Rose’s room and put it around her legs before wheeling her through a maze of walkers up to a place at the table next to Molly Gwynne.

As she put a bib on Rose, a hand came up and touched her. Molly said pathetically, “I want to go home.”

3

Bess resisted saying, “We all do,” asking instead, “What’sa matter, Molly? Aren’t ya happy here with us?”

Molly shook her head. “That’s not it. I need to be home.”

“Where’s home?” Bess asked, knowing Molly would be forgetting the tiny apartment here in town from which she’d entered the Rest Home and was thinking of the family farm instead.

“Well, you know!” Molly grew petulant, pointing her finger over her shoulder. “Down the lake, on the hill.”

Kathy was giving Bess a look from the kitchen, wanting help. Bess said, “Molly, my love, ya left the farm years ago. Gave it to your son and moved to town.”

“I didn’t give it to him!” Molly’s face grew fierce. “Only to farm it. I should have a place to live. It’s his wife…,” and she began to cry.

Kindly, Lydia, who was sitting across from Molly, leaned forward and said, “This is your home now, dear,” and Bess hurried to the kitchen. The snow was still falling.

At a few minutes past nine, Dee flounced in and went upstairs to her office. The only residents left in the dining room were Ishbel, Rose and Louisa. Willow was down the hall calming Mary who was sure her money’d been stolen while she ate breakfast. Bess was wiping Rose’s face when Dee came down and said, “Haven’t started the baths yet?”

“Not yet.”

“‘Dee’ is for director,” Dee had said her first day at the Rest Home in an attempt at light humor. Some directors (Bess had been through four) tried to be friends with the staff, others preferred to maintain distance and thereby authority. They all said the low wages for the “girls” on the staff were

4

scandalous, $8 an hour with a lousy ten-cent raise per year, but none of them was able to persuade Dr. Burns to pay a higher wage. He claimed he lost money on the Home. The residents were too poor to pay more. Bess’s salary was now eight miserable Canadian dollars and seventy cents an hour. She wondered what Dee’s salary was. Dee was a qualified nurse. No more “beds, bums and baths” for her. Bess wished she had the time and money to get more training, but even if she did, there were almost no jobs to be had in this part of Ontario.

“Mary lost her purse again,” Bess said, hoping Dee would handle the search and let Willow get back to their morning’s work, but Dee was on her way to the kitchen to talk to Kathy.

Rose had eaten almost nothing. They hadn’t put her teeth in this morning. She didn’t really need them for orange juice and porridge, yet most of what Bess had tried to get into her ended up as sticky dribble on the bib. “Can ya smile for me, Rose?” she asked and watched the old eyes search for her face, the muscles beside her mouth lifting slightly. “That’a girl.”

She carried the dishes out to Kathy. Dee was still there. “We should call Rose’s family,” Bess said.

“Why?” asked Dee.

“I just think she’s going downhill, like?” Bess said. “She won’t eat this mornin’. Hasn’t tried to speak.”

“She has good days and bad,” said Dee, going out to take a look at Rose, who opened her eyes when Dee spoke to her. Dee had a gentle quiet way with the elderly that often made everyone feel better. “I don’t know,” she said now. “Peggy was here a week ago and saw how her mother is, how much weight she’s lost. I don’t think we have anything new to tell her.”

5

“O.K.,” Bess said and wheeled Rose down the hall toward the bathrooms, almost running into Mary as Willow pushed her chair into the hallway.

“Where’d she hide it this time?” Bess asked.

“Under the mattress,” Willow said. “Is that all of them?” In the second sitting room across from the bathrooms a line-up of wheelchairs faced the television.

“All but Ishbel and Arthur. Why don’t you bring Ishbel up and I’ll get started with Rose,” Bess said, pushing Rose toward the larger bathroom.

“Why Rose first? Mary’s family is coming today.” “Because Rose is the first one up and she’s cold.” Willow was moving down the hall and shrugged.

“You’re going to feel warmer when we get you into the shower,” Bess told Rose, rubbing her scalp lightly, that being the only place on her body that the old woman still seemed to take comfort from having touched.

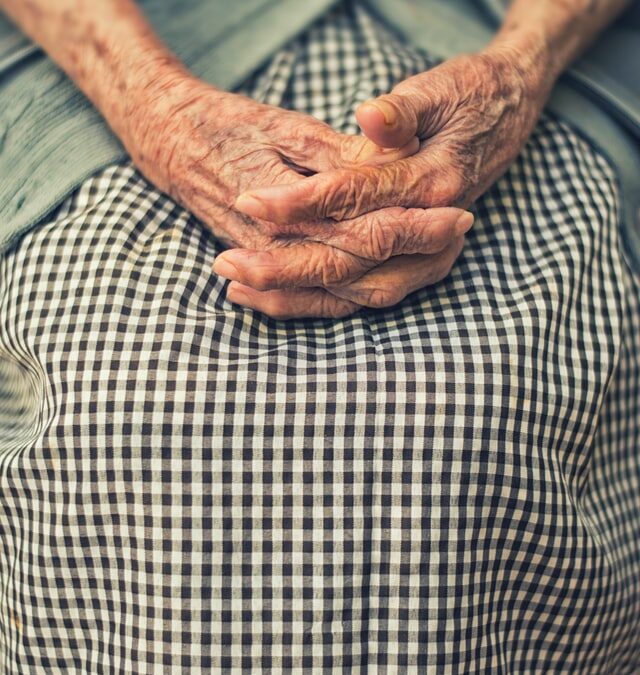

Bess and Willow were stripped to their underwear, wearing towel smocks, as they undressed the old woman. Her long legs were just bones and skin now, a sharp white line of a shin, and there was little flesh on her hips or belly, but her white hair was still beautiful. She remained silent while they washed and dried her. They wrapped her warmly in a blanket and Bess wheeled her to her room and lifted her onto the bed, where she sank her head into the pillow, eyes closed. Bess would have liked to join her.

They were just lifting Mary (who had Alzheimer’s and was particularly resistant), struggling to remove her clothes, when Kathy came from the kitchen to say Bess had a phone call from her son.

6

“Which one?”

“Peter.”

Bess looked at Willow. They knew one another’s griefs. Their boys had gone to school

together, played hockey together. “I can’t take the call. What does he want?” “Truck won’t start.”

“Tell him to wake up his father.”

Willow just shook her head and smiled as they carried Mary to the toilet. Willow was short and stocky and couldn’t lift people very well. Mary’s feet dragged across the floor.

“He’d rather I deal with it than Doug,” Bess said unnecessarily and fiercely craved a cigarette. “You’re on the toilet, Mary,” yelled Willow, listening for the telltale sounds, but the old

woman looked confused. Finally they carried her in and put her on the shower stool. Bess held the spray and lifted Mary’s arms one by one while Willow tried to wash her. When they lifted her to wash her bum Mary cried out, whether in pain, fear or outrage, Bess wasn’t sure. It was like showering Holocaust victims, torturing these old people, the skin of their arms and legs so thin that a mere tap bruised it. When they had Mary out and were drying her on the other stool, she pooped and they had to put her back into the shower.

Bess and Willow were finally pulling on Arthur’s socks and shoes when Kathy came down and said it was time to bring the residents back up for lunch. No time for a break. As Bess stood up, she steadied herself against the edge of the sink and saw what she looked like. “I forgot to comb my hair,” she said, realizing as she said it that it made no difference.

7

For twenty-two residents there were two workers on the floor, a cook and a director. Together they got everybody back to the dining room in ragged fashion, then Dee disappeared back upstairs with a plate of food. Someone needed changing, Bess could smell it, but that would have to wait. Chicken, mashed potatoes with gravy, and peas. Some residents wanted bread and butter; some didn’t want peas. They couldn’t manage peas very well. There’d be peas on the carpet after dinner. Kathy put the food on plates and Willow and Bess rushed around serving, pouring tea or coffee, water or milk, tying on bibs, crushing up pills for those who couldn’t swallow them, and stopping now and then to try to feed Ishbel, Mary or Rose. Willow had put Rose’s teeth in, but she still didn’t want to eat. Her eyes were closed and she wouldn’t open her mouth.

By the time the last people were served, the first were finished and ready for their butter tart. Bess, on the fly, finally got Rose to take a tiny taste of the dessert and nod when Bess asked her if it was good.

Beatrice couldn’t get out of her chair. Her knees were swollen with arthritis, but she seemed in a hurry to go back to her room. As Bess lifted her up, she said, “There ya go, Bee.”

“I’m not ‘Bee!” Beatrice protested.

“O.K. Beatrice.” Bess pulled her walker over closer. She knew Beatrice had told Dee she’d always preferred “Bee” or “Beatrice” to “Trish,” so that’s what they were supposed to call her.

“Trish. Trish. I’ve been called Trish all my life!” Beatrice hit the handle on the walker with her palm in her anger.

“You can be anything you wanna be-e-e, Trish,” Bess punned. “Bee Trish, that’s what we’ll call ya.”

8

“Hmph. You can’t hear what I call you!” Beatrice turned her back and moved away, now that she was up on her feet.

“Well, I hope it’s somethin’ nice,” Bess called after her. Next to her, old Winnie, deaf as a stone, smiled at her like a saint.

Bess and Willow had to clear dishes, change diapers and bed a few residents for a nap before they could eat their lunch. As Bess was wheeling Ishbel to her room, she saw Molly in the second sitting room, flanked by her two sons. Molly looked up at her with a broad smile on her face, not a word to say about returning to the farm. “Both sons at once! A happy day,” Bess said and greeted the two men, both in their sixties. They told her the snow had accumulated to about a foot, then went back to watching the ice skating on television, not having a clue how to talk to their mother.

When they’d finished, Willow and Bess sat upstairs in the staff room with a barely warm meal, not talking much. Bess smoked two cigarettes. She could hear the scrape of the snow shovel as Kathy worked at clearing a walk from the door to the road. Less than three hours to go.

While Lucille announced page numbers in the Christmas carol books and haltingly banged out old favorites on the piano, Bess and Willow took laundry out of the dryer, put the wet clothes that the night girls had washed into the dryer and started a new load of wash. Folding the dry clothes, they looked out at the still falling snow. Over on the lake boys were shoveling off a rectangle between their hockey goals.

9

Before their shift ended, they got up the ones they’d put down in bed. The oldest ones napped most of the time whether they were sitting up or lying down, but it was important to change their positions. When they’d changed Ishbel and Willow was wheeling her out, there was only Rose. Bess went into her room calling, “Rose, are yuz ready to get up?” She put on a fresh pair of gloves and took a fresh diaper out of the closet. Still Rose’s eyes were closed, and Bess stroked her white hair. When Rose first came to the Rest Home, she’d been cheerful, insisting upon helping out where she could, saying kind things to show her gratitude. Then age had worn her down, taking away any self-sufficiency she had left, taking away her dignity and her kind words. There was never a happy ending. One day, Bess thought, she’d be in here herself.

“Rose?” Bess said and put the back of her gloved hand against the old woman’s cheek, then along her arm. It wasn’t impossible for her to be unresponsive, but Bess somehow knew that Rose was gone. She watched closely for breathing and put her hand along the carotid artery. There was no sign of life.

Leaving the room, she met Willow in the hall. “I think Rose is gone,” she said. “I’ll go tell Dee.” Willow said “Oh-h-h” sadly, then just stood there, and Bess guessed she was realizing she was done for the day.

Dee came down and confirmed Bess’s conclusion. She called Dr. Burns at the clinic on her cell phone and directed Bess to go to the phone in the office and call Rose’s daughter. The contact numbers were next to the phone. Peggy’s husband answered but Bess asked to speak directly to Peggy. “I’m very sorry,” she said, “but your mother just passed away. I went in to get her up after her nap and she’d gone.”

“What?!” Peggy sounded angry. “Why didn’t you let me know she needed me?”

10

“It’s really hard to know. She had good days and bad days. We knew’d you was here recently and saw she was fading.”

“Fading is different from dying!” Peggy said. “We were going to come but for the snow,” and she began to cry.

Bess left the Home just as the doctor arrived, half an hour after her shift was supposed to end. She had a list to buy at the grocery store before going home to make supper. Willow had just finished digging out of the snowbank thrown up by the plow. She said goodbye and drove away as Bess got her shovel out of the car. The snow wasn’t terribly heavy but there was a lot of it, still some flakes falling. She lifted mounds away from her front wheels, heaving them over the bank onto the sidewalk. When she thought her car could muscle its way back into the cleared lane, she tossed the shovel in and got behind the wheel, pulling off her mittens and fumbling into her bag for a cigarette, her cold hands numb.

Drops of water fell from her hair and made tiny sizzles as she lifted the match. She rested her head against the back of her seat and inhaled, enjoying the quiet, the lack of motion, thinking about Rose’s daughter, how guilty she’d felt because her mother had died alone. The light was waning. She blew the smoke at the still snow-covered windshield. A grey shroud. A closed eyelid.

*Originally published in Blue Ridge Anthology, 2009*

Carolyn McGrath has an M.A. in creative writing. Her fiction has appeared in North Atlantic Review, The Blue Ridge Anthology, Flash Fiction Magazine, and Cat Fancy, and her memoir Queenbird was one of six titles shortlisted for the Faulkner Wisdom Prize in creative nonfiction in New Orleans in 2017. Her book, Two Faces of the Moon – A Small Island Memoir, is scheduled for release on July 24, 2023 by Brandylane Publishers.