Ever since Sarah was born blue and floppy and her cardiologist father resuscitated her, I have imagined a disaster. After Ben appeared, five years later, limp from my labor pain meds and large from my ice cream intake, a steady humming tension surfaced.

I was never alone, nursing this fear of what might happen to my kids, imagining marbles lodged in airways, open gates to neighborhood pools, all-terrain vehicles T-boning trees.

Mamas in some other places are terrified their kids will fall down wells, be eaten by alligators, suffocate from air pollution, succumb to lead poisoning, drown in sewers, slip off the top of that monster train hurtling through Mexico.

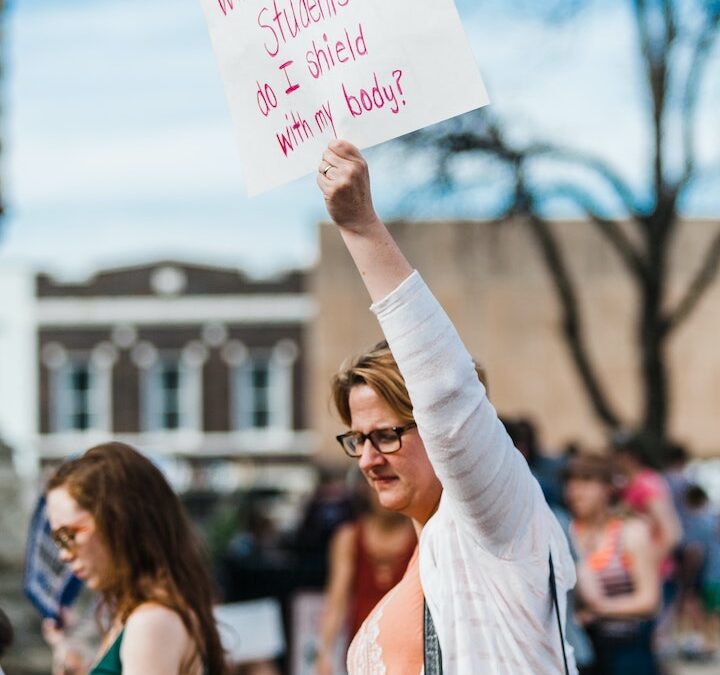

And then, here in America, the radio reports a fifteen-year-old boy down in the middle of a park or a toddler on the way to the hospital after finding a gun inside a shoe box. We watch videos of small children exiting schools after shootings, looking vulnerable and scared, arms over their heads proving they aren’t carrying firearms.

Mamas here, and Mamas there, watch the news, or turn off the news, pound their steering wheels, or scream into their computers.

“You can’t leave that sign there.”

I’d already moved down the hall on the third floor of the Kentucky capitol building in Frankfort, away from our Advocacy Day assigned room, which didn’t work out because water pipes had burst.

Now, a tall older man in dark gray clothes stood looking at our 5-foot-tall rectangle leaning against the railing, frowning at the photographs attached to the orange-papered Survivors Board.

“After 1:00. It can’t be there after 1:00.” He gestured towards the entrance to the Senate chambers, a wordless explanation.

Oh. Wouldn’t want politicians to see faces of kids killed with guns.

“Turn it around,” I say to Melissa. “So, they can’t see the pictures.”

We pause, looking at one another. Not an hour before, at our gun violence prevention gathering in the Capitol Rotunda, some of our members—mothers of those dead children—stood facing the crowd, holding up the Gun Violence Survivors Board, insisting everyone look at those photographs—local TV station cameramen, newspaper reporters, teenagers leaning on stairs, legislators walking by.

Melissa twirls the unwieldy bulletin board so the faces are in shadow, up against the marble banister, and then the back side—the blank gray canvas of construction insulation—parallels the Senate door. The older man stays with us but seems less concerned now about the view.

A short woman in a straight skirt comes out of an office and points towards the folded pop-up event table, large cardboard box, and plastic crates holding manila envelope Advocacy Day packets. “You can’t leave those here.”

“We don’t have any guns,” a fellow volunteer barks, then looks away and whispers, “Sorry. I couldn’t help it.”

Loaded firearms are permitted throughout the Capitol grounds, but umbrellas and signs on sticks are confiscated.

The woman goes back into her office, then returns and offers to find a rolling cart, to help us navigate exiting the Capitol building with all our stuff. To help us leave.

When Sarah was at college in Ohio, I woke one morning to a news story about exotic animals being loose not far from my daughter’s college and I texted her a message, to not go out on an exercise run, right this minute. Please walk, don’t run, to class. A leopard might mistake her for a deer. She hadn’t heard the local reports and had already walked to class when she read the strange message from her mother. I imagined her reading it aloud to a classmate and laughing.

Years ago, I was filling up at a gas station when a second car pulled up on the other side of the pumps. As the young man got out of his vehicle, the air filled with a joyful noise, the kind of song that makes me want to lift my arms and twirl. I exclaimed, loudly, “Who is that? What is that song?”

The young man’s eyes widened, unsure if I was talking to him. Unsure if it was a serious question.

The music was loud. Loud enough that he probably worried I was about to complain, this middle-aged lady in a minivan.

But I wasn’t complaining.

“What is this song?”

He looked directly at me and paused. “It’s Shaggy. ‘Angel.’ It’s called “Angel.’”

I laughed, thoroughly delighted. “’Angel.’ Thanks.”

The young man’s consideration of me—his pause before his reply—stayed with me, worrying me, calling up the story of Jordan Davis, who drove up to a Florida gas station with his friends in 2012 and was shot dead because they were playing music too loud for the old man with the gun. So, whenever I hear “Angel” playing, I imagine the mother of Jordan Davis, and then the mother of the young man who was playing Shaggy’s song at full volume at the River Road gas station.

Now there are three older people in dark conservative clothes standing beside the large insulation rectangle in the Kentucky Capitol overlooking the grand rotunda, a second man and a woman having joined the first.

“We’re all retired state troopers,” the first one tells me. “We do this part-time.”

Capitol Security.

When the two men walk away, no longer concerned about the blank board facing the Senate chambers, the retired female trooper asks me, “So, what does your group want?”

And I tell her, careful with my choice of words, that we want to keep families safe, and we advocate for secure storage of firearms in the home and for policies like background checks for all gun sales, for keeping guns away from people who are dangerous to themselves, or to others.

She listens with serious eyes. No smile, no frown.

When I stop speaking, she says, “I would have no trouble with any of that.”

Then she walks away, down the hall.

I stay, guarding the mothers’ display board, all those faces turned towards the marble.

Almost twenty years ago, when my children were children, I went with a friend to an afternoon movie showing of The Passion of the Christ. With a box of popcorn in my lap, I started watching the gruesome tale, the Easter story I’d long ago absorbed during my Southern Baptist upbringing. I had no premonition of dread. The story was old and familiar, celebrated by small children each spring.

I did not make it past the whipping of Jesus.

Not because of the story. Because of Mary’s face. The camera lingered on the mother’s face, tear-stained and wounded, watching the jeering of her child, the brutal beating of her son. Helpless to do anything to stop his murder.

I couldn’t bear her grief.

I abandoned my popcorn and my friend and fled the theatre and sobbed alone, sitting on a hall bench. I cried for his mother, for Mary, for her despair.

Richard Blanco, in his poem “House of the Virgin Mary,” describes visiting the site reported to be Mary’s home in Ephesus, Turkey. He lights a votive candle, not for any religious reason but “. . . simply because she was, after all, a mother.”

If you’re lucky, your kids get older. They may leave home. Join the military or go away to college or move to another town to work. Or fly far away to volunteer for a non-profit on another continent. And, it feels like someone reached into your abdomen and withdrew a vital organ, one that you needed to survive.

But you keep waking up each morning, even though they’re gone. Sometimes you think you hear a chair move upstairs, like they’ve pushed back from the computer. Or you hear their closet door shut, or the upstairs toilet flushes by itself, and you get goosebumps, wishing they were home. Wishing they would visit.

If you’re lucky.

Laura Johnsrude’s essay, “Drawing Blood,” was published in the spring 2018 Bellevue Literary Review, winning Honorable Mention for Fel Felice Buckvar Prize for Nonfiction. She’s been published in Hippocampus, The Spectacle, Please See Me, Fourth Genre, Good River Review (book review), and in a recent collection, The Boom Project anthology.

Laura Johnsrude’s essay, “Drawing Blood,” was published in the spring 2018 Bellevue Literary Review, winning Honorable Mention for Fel Felice Buckvar Prize for Nonfiction. She’s been published in Hippocampus, The Spectacle, Please See Me, Fourth Genre, Good River Review (book review), and in a recent collection, The Boom Project anthology.