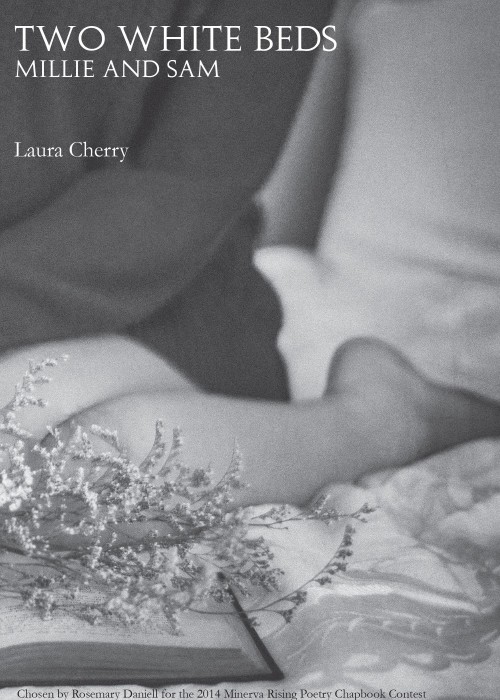

Editor’s note: Winner of Minerva Rising’s inaugural chapbook contest, Two White Beds by Laura Cherry is a collection of poetry that dares. It tells the story of two young Victorian women, Sam and Millie, who fall in love and must then decide how their stories will unfold.

We lucky readers are brought along on a train ride to another age, through history, persimmon groves, “months as a laudanum haze” and “dark nights that breed strange illusions.” With erstwhile language, poet Laura Cherry captures the timeless sense of being wrapped in an emotional maelstrom with no clear way out.

In clear, first-person voices, the two characters’ passions for each other smolder in subtlety with a tense clarity that is both veiled and intense.

Here, Laura Cherry blogs about what it was like writing Sam and Millie’s story.

***

It started as a project, a month-long commitment to write a poem a day on a postcard and send it to another poet, while also receiving a postcard each day. The prompts are built in: the images on your own postcard, the images on the postcard you receive, the received poem, and the whole world around you. The poems must be short first drafts, relieving the pressure to impress. I began with some lyric complaints, nothing too challenging, keeping copies for later revision. One morning, early in the month, I wrote a poem in someone else’s voice. I don’t mean to sound creepy or mystical; it wasn’t like that. A character wafted in and I foggily first-drafted her before she wafted away.

I wrote from one young woman to another. Something Victorian was happening, something British. The women were in love. Their names were Millie and Sam. I finished the draft and mailed it.

Without planning to, the next day I wrote from the other young woman’s point of view. Millie and Sam had a number of things to say to each other. Very soon, Sam was going away to spare Millie’s reputation. Miserable but resolute, she found factory work in London. Millie languished at home, furious, jealous of Sam’s freedom, hating her own life. I wanted to see how long I could keep their conversation going.

Sam and Millie had distinct voices, faces, histories to me. Sam wrote in a rush, speaking plainly and openly. Millie’s notes were fiery, more oblique, more crafted. Some days, I’d take an image from a postcard to help them say what they meant. Open window. Lion and egret. Ladybug. It was their own small-scale mythology. I finished the month and set the poems aside.

The arrival of these characters gave me a taste of what it’s like to write fiction, to describe a different world from my own. Literarily, Sam and Millie come from every Victorian novel I’ve ever read, wondering about the lives they conceal. They come from watching Lianna and desperately wishing for another ending. They come most clearly from the novels of Sarah Waters, who dares to imagine lesbian lives – happy ones! – in the gaps of the historical record.

Later, I returned to see how I might complete Sam and Millie’s story. I wrote far more poems than I could use. I brought in side characters, supportive or disapproving. Sam found a dog, moved to a boarding house. Millie fretted about her position, cold-shouldered suitors, described a painting she’d seen of St. George and the dragon. I was glad for these poems, but I cut many of them away in the end.

When I’d pruned their story down to the cleanest one I could make, I fact-checked. There were things about their backstory that I knew but didn’t write: their different classes, how they’d come to know each other, their family lives. I tried to include enough detail to orient the scene without drowning it. I don’t hope for scholarly accuracy, but I didn’t want to make any truly ridiculous mistakes. I hope I haven’t.

Now they are in the world, or the world is in them. I’m glad they get to tell their story, and grateful that, due to so many courageous acts and books, it isn’t controversial or shocking now to tell it. Sam and Millie’s lives are quiet, but brave in their own way. I’d make a bad novelist; I didn’t have the heart to keep them in trouble any longer than I absolutely had to. It was my luxury to give them the happy middle they deserved.

***

Laura Cherry is the author of the 2014 chapbook Two White Beds (Minerva Rising), the full-length collection Haunts (Cooper Dillon Books) and the chapbook What We Planted (Providence Athenaeum). She co-edited the anthology Poem, Revised (Marion Street Press). Her work has appeared in various anthologies and assorted journals. She lives near Boston, where she works as a technical writer.