A 1975 ad for Buxton women’s wallets asked, “What better way is there to organize all those things you have to carry?” Buxton’s offerings included the Victorian Super Clutch in “ostrich grain split buffalo calf” with “elegant hand-tipped markings of a slightly deeper hue” or the Terra Convertible Billfold with “hand-rubbed variegated finish that’s most appealing.” My mom embraced fashion and believed a woman’s purse should match her shoes, but she would have scoffed at Buxton’s catchphrase, “What you hold in your heart belongs in a Buxton.” Her wallet was a tool, not a fashion statement.

Not that she didn’t pick hers out with care. Whenever her wallet started to look a bit frayed, we went to The Bon Marché Women’s Accessories Department for a new one. My mom bypassed the luxurious leather wallets dyed in turquoise or cobalt, the ones festooned with simulated pearls and cut crystals. She went straight for the Lady Buxton checkbook clutch in caramel leather with a button snap, inside pockets for money and cards, outside zippers for change, and a slot for her checkbook and ledger. The clerk nestled the top onto the box and wrapped it in tissue before slipping it into a handled sack. Once we were home, she transferred her cash, checkbook, Texaco, and Bon Marché credit cards into the slots, snapped it shut, and tossed the old wallet unceremoniously in the trash.

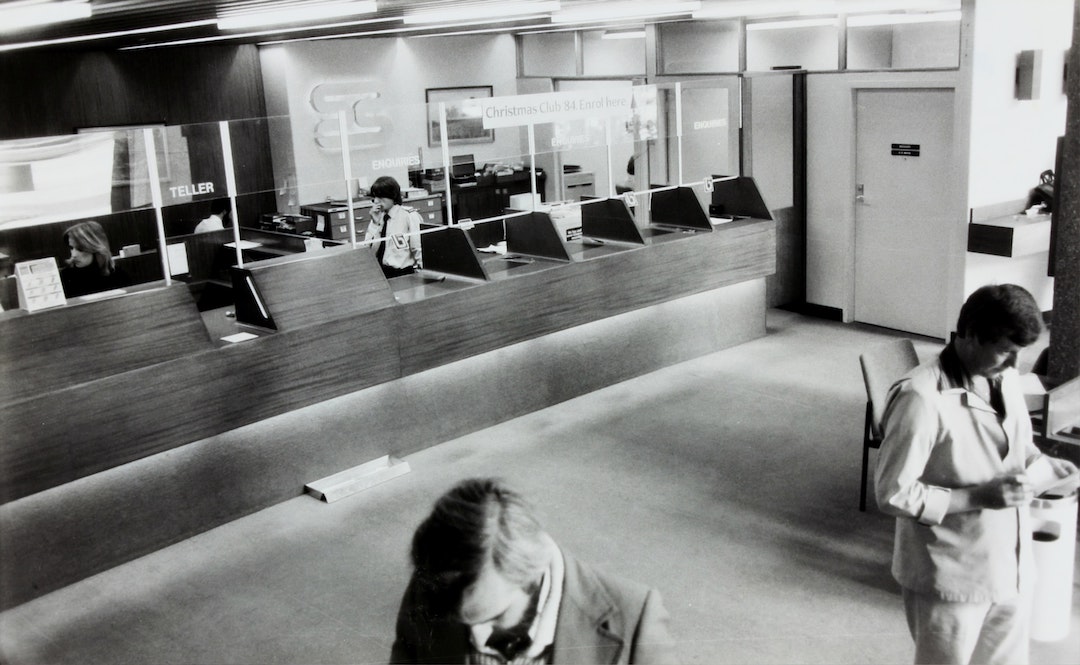

In 1976, when I was 16, my mom took me to the bank to open my first checking account. We walked across the hushed carpeted lobby and sat in two soft chairs in front of a large walnut desk. The bank officer slid papers across her polished desk, and my mom signed and slid them back. I was handed a blue plastic checkbook with blank checks inside. Once we were home, she ushered me to the kitchen table and sat beside me with her checkbook, bank statement, and a small stack of mail. She opened an envelope, smoothed the bill out in front of me, and pointed out the amount and due date. In her flowy handwriting, she wrote Washington Water Power Company. She tapped the words with her pen. “You write in cursive, always.” She wrote the date numerically with clear slanted lines. “If you’re late paying a bill, it affects your credit.” The amount was entered in the small box and written in cursive on the line below. Any cents were written numerically, with a firm line drawn across the blank space so the check couldn’t be altered. Fifty-Three Dollars and 22/100——–. And at the bottom, her firm hand looped the letters in her signature, punctuating the last two T’s in her last name with a bold line. She flipped to the last page in the ledger and entered the date, payee, and amount, subtracting it from the balance.

My boredom must have been obvious.

Her coral lipstick thinned into a tight line. “You’ve got to have good credit. If you get in trouble with your money, you lose your credit. And credit is everything.”

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act had been enacted two years earlier, but my mom didn’t need it to tell her the value of good credit. Her childhood had been spent in a remote logging camp in western Washington. On Saturday night, her family would drive to the nearby city of Bellingham, and her father would spend the evening at the poker table while the rest of them went to a movie. “If he won big, we got to go to dinner and a second movie,” she recalled. “If he lost, my mom and I went to the loan officer.” Her family’s finances were built on a shaky foundation of uncertain paychecks and high-stakes card games. Watching her timid mother beg for money to pay the bills was both personally humiliating and a frightening way to live.

My mom longed for security and stability and took matters into her own hands. After high school, she worked at a dress shop to save enough money for college tuition, though her father thought college was a waste of time for a woman. In addition to her courses in history, typing, and sociology, she also took one called “Marriage and Home” where she was taught nutrition, childcare, and personal finances. She learned credit was trust in a person’s ability to pay for goods and services. A person establishes credit by paying bills on time and living within a budget. With a strong credit history, a person could rent an apartment, take out loans for a house or car, even get a better job. Good credit led to a life of security and wealth.

In the middle of her second year of college, she dropped out to marry my dad. This was an entirely respectable college career for a young woman in 1951. My mom was considered an educated housewife who would manage the household as her husband built his career. So while my dad worked his way up the Procter and Gamble advertising ladder, my mom took care of three kids, the home, and his paycheck. She was responsible for the family finances, from bill-paying to insurance claims, and took great pride in her skills. She could add and subtract in her head and see at a glance if the math was off. And if it was, even by pennies, she went over the numbers until she got it right. One mistake or misstep, she worried, could endanger the family’s financial security.

She always said her job was to keep us out of “The Poor House.” As a child, I envisioned a concrete building filled with steel beds and sad people in tattered clothes. My mom also talked of living in “The Downtown Apartment with the Bare Lightbulb,” presumably the home for people one step away from The Poor House. I always laughed, because I knew her brain and precise math would keep our family out of both. Each month she sat at the dining room table with a stack of bills bound by a rubber band, a roll of stamps, and crisp white envelopes. She opened her checkbook and scratched away with a blue pen under the glow of the hanging light. We were not to disturb her at this time. When she finally pushed her chair back, there was a tidy stack of stamped envelopes on the table.

A more important refrain, the one she reserved for my sister and me, was “Never Depend on a Man.” My mom’s voice, both determined and bitter, made me ache with love and worry. Was she unhappy? Was she afraid? Did she regret her life?

She was terrified.

Her marriage to my dad was built upon the breadwinner-homemaker model, and it worked well in the decades where divorce was socially condemned and not always easy to get. But no-fault divorces in the 60s allowed a man to divorce his wife without cause or her consent and did not guarantee a fair settlement, alimony, or child support. Her friend Helen went through a nasty court battle after her husband left her for a younger woman. “Helen put him through law school,” my mom fumed, “then he and his lawyer buddies made sure she didn’t get a dime.”

Helen’s situation could too easily be hers. The checks she wrote came from a bank account she didn’t own from money that was not legally hers. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act allowed her to use household income to apply for her Bon Marché credit card, and her accounts couldn’t automatically be closed if my dad died or divorced her. But without his income, she couldn’t afford to keep them. As a housewife still raising children, she would have found it difficult to get a job with enough income to pay the bills.

When I was hired as a high school English teacher, she glowed at my contract with its annual salary and generous benefits but reminded me to properly manage my money. Each month I deposited my paycheck and entered the amount in its ledger. I made a chart of my monthly bills, their amounts, and due dates, sat at the kitchen table in my apartment, and wrote checks for each one. The stacks of bills grew larger to include monthly payments for a Toyota Celica and a $2,500 Apple computer. I moved to a high-end apartment with its own washer and dryer, a fireplace, and a deck overlooking a golf course. Visa and Nordstrom’s issued me credit cards, the ATM machine spit out crisp bills for nights out with friends. One month, I paid my bills and the math didn’t add up. I was almost two hundred dollars short.

My mom’s silence on the phone spoke volumes. Her daughter had failed to live within her means. “I’ll give you the money,” she finally said in that tight, disappointed tone I recognized. When the envelope in her handwriting arrived in the mail, I felt sick. I pictured her writing out the check in her graceful cursive hand and adding it to the stack of bills. Subtracting it from the ledger in her leather Super Clutch wallet. Snapping it shut with her mouth in a tight line. Never again did I spend more than I earned.

After my dad died, my mom’s mind started to unravel. We would go to her house and find her sitting on the living room floor sorting through stacks of bills, insurance policies, and bank statements. She flipped through her checkbook ledger, confused at the dates and the amounts and who she had paid. “What is this bill from American Express?” she demanded. “I don’t owe them any money!” We couldn’t convince her it was only an offer for a new credit card. She glared at us and continued to stare at the paper, brow furrowed. If we tried to help her, she became suspicious and argumentative. Alzheimer’s had robbed her of the power she fought so hard to attain, and now we had to take over her life.

I walked into the hushed carpeted lobby of my bank with the same reverence I had at sixteen. The bank officer looked over the Power of Attorney and I signed the paperwork giving me control of my mom’s accounts. When she handed me the blue plastic checkbook, I felt a pang. I grieved for the loss of my mom’s keen mind, her strength, her humor. It felt invasive and impersonal, writing checks with my mom’s money. As though she were already dead, not alive in a Memory Care facility. I tried to imagine her assuring me I was just doing what needed to be done. I also remembered her determined walk across the bank lobby to open my checking account and her proud voice telling a friend about my first job.

My mom understood the strength of financial power and believed a woman without her own money had no power at all. Though most of my bill-paying is done online, I remember my mom at the dining room table with her head bent over the checkbook whenever I need to write a check. I hear the scratching of her pen and see her graceful handwriting on the stacked envelopes, paying bills with money that was never her own. I draw a firm line across the blank space, raise my pen in a grateful salute to my mom, and snap the wallet shut.

Darcy Lohmiller’s work has appeared in Manifest Station, Michigan Quarterly Review Online, The Drake, Big Sky Journal, The Fly Fish Journal, Shooting Sportsman Magazine, and other publications. She lives in Bozeman, Montana.